A presentation given in History on 5 September 2023, 9-10 am,

at U3A Brisbane/Australia

|

| Gabriele Münter (1877-1962), Hauptstrasse (Mit Mann), 1934 |

Impressionism c 1865–1885

1863 marked the birth of the avant-garde in Paris. From 1874 onwards the Salon’s increasingly conservative and academic juries usually rejected the works of Impressionist painters.

This resulted in separations and 3 major Secessions, that were to spread throughout Europe.

The forerunners of the Impressionist movement shared interests in

painting ‘from life’, outside in the countryside, favouring landscapes and

social situations over grand, overly dramatic scenes. However, unlike Realism,

which placed importance on representational honesty and a photograph-like

appearance, Impressionism was not just a movement. It introduced new visual and

technical styles for paintings that emerged in 1870s France and became popular

for the next 50 years.

It originated with a group of radical Parisian painters, who gained fame

for their violation of the rigorous rules of academic painting that fostered

carefully finished, realistically precise paintings. These radicals sought to capture the

immediate impression of a particular moment. They used modern

life as their subject matter, painting situations like dance halls and sailboat

regattas rather than historical and mythological events. Key features are the fine, light, highly visible

brushstrokes that wash across the paintings, characterised by short,

quick brushstrokes and an unfinished, sketch-like feel. Attention to the accurate depiction of the light throughout the day or

night was important.

Artists were initially heavily criticised and could not exhibit at the

prestigious Paris Salon. Therefore, they founded the Cooperative and

Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, where they

could exhibit independently.

In derogative response to an exhibition of Impressionist works, the term

‘impressionist’ implied these works to be merely an impression, instead of

being solid and meaningful.

|

| Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872 |

It was after his work

Impression, Sunrise, (1872) that the entire movement was named. Monet

is famous for his landscape scenes and his paintings of gardens, particularly

waterlilies, in vibrant, pastel shades.

|

| Claude Monet, The Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874 |

The Impressionist movement coincided with significant advances made in paint technology. Premixed paints in new, vibrant colours became available in tubes, allowing artists to work more spontaneously and easily outside.

In some Impressionist paintings, there are even grains of sand or blades

of grass that became stuck to the canvas whilst the artist was working

outdoors.

Another important Impressionist artist, who bridged the gap between Realism and Impressionism, is Édouard Manet (1832-1883).

Manet painted several highly controversial works that subtly use Impressionistic techniques and yet capture the essence of the movement. This painting was initially highly criticised, not only because the woman is nude, but in her nudity, she dares to focus her gaze on the viewer.

This was perceived to be distasteful.

|

| Vincent Van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses, 1889 |

Post-Impressionism was the last significant European artistic movement of the 19th Century, which again took place predominantly in France between 1886 and 1905.

The movement was born out of many artists’ dissatisfaction with the

blurred, blended appearance of Impressionist subjects and compositions, which

they thought lacked structure. The Post-Impressionists sought to restore order

and structure to paintings, to make solid, durable art that celebrated a

distinct, artistic style. The painters worked independently rather than as a

group and instead of an overarching style, the artists developed a wide range

of styles and techniques, but each

influential Post-Impressionist painter had similar ideals.

Post-Impressionists

concentrated on subjective visions and symbolic, personal meanings rather than

observations of the outside world. This was often achieved through abstract

forms. Their paintings were unified by their

emotive qualities and rich symbolism. Thick, painterly brushstrokes

characterised many Post-Impressionist paintings, and were arranged in orderly,

directional patterns to make up a composition.

The colours used were bold and vivid, bordering on unnatural vibrancy. Subject matter ranged from landscape painting to still life, encompassing genre scenes and social compositions as well.

Post-Impressionist painters include Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891), who was noted for his pointillism technique using small, distinct dots to form an image.

|

| George Seurat, A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884 |

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) characterised the period with his impulsive, tangibly expressive brushstrokes, bold colours, and highly emotive works, ranging from his self-portraits to still life paintings to landscape scenes.

|

Paul Gauguin, Vahine no te tiare (Woman with a Flower), 1891 |

|

| Henri Rousseau, Le Moulin (The Mill), c 1896 |

The legacy of 19th Century painting is immense. The huge changes toward artistic freedom that occurred in the final decades of the century paved, without doubt, the foundations for the contemporary art world—and indeed the art market—that we enjoy today.

In all their diverse styles, these paintings are some of the most

collectible artworks ever made, with names like Van Gogh and Monet now reaching

unthinkable sums in auctions.

Worpswede Artist Colony 1889–2023

A group of artists like Fritz Mackensen, Otto Modersohn, Heinrich Vogeler and poets like Rainer Maria Rilke wanted to escape from the modern world with its chaos of industrial cities to find solace in the country. They found the farming village of Worpswede (Northern Germany) to be a source of inspiration. They formed an artists’ colony in 1889.

|

| Otto Modersohn, Worpswede, 1910 |

These artists sought

refuge there in the bog landscape with its open plains, wide skies and sunny days. In this colony the group thrived

by copying the plein air painting from France.

Paula Becker found the picturesque village inspiring. Compelled by the remote location and the harmony of the artists’ colony, she decided to move there and start taking lessons in drawing and painting. She eventually married Otto Modersohn.

|

| Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, 1906 |

Paula’s art was ahead of its time, being decidedly expressionistic. She is today considered a leading representative of modern art.

|

| Heinrich Vogeler, Sommerabend (Das Konzert), 1905 |

Art Nouveau c 1890-1910

|

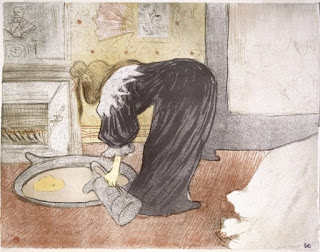

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Woman at the Tub from the portfolio Elles (1896) |

Influential Art Nouveau artists worked in a variety of media, including architecture, graphic and interior design, jewellery-making, and painting. Famed French-artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was at its helm.

|

| Alphonse Mucha, Princess Hyazinthe, 1911 |

Still standing in tribute to the Art Nouvea era are Spanish architect and sculptor Antonio Gaudí’s (1852-1926) curving and brightly-coloured Basilica de la Sagrada Familia (1882-2026) in Barcelona.

|

| Detail of the roof in the nave. Gaudi designed the columns to resemble trees and branches. |

|

| Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905 |

Other notable Fauvists include André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958).

|

| Maurice Vlaminck, Sailing Boats at Chatou, 1906 |

Secession movements

|

| Egon Schiele, Poster for 49th Secession Exhibition, 1918 |

The term ‘Secession’ was coined to describe the spirit of various art movements towards the fin de siècle. Disillusioned with old-fashioned European viewpoints in art, artists separated from the official Artists’ Associations. They established Secessions in Munich, Vienna and Berlin after the Paris breakaway.

Münchner Secession 1892-1938; 1946-present

The Munich Secession was an association of visual artists who broke away in 1892 from the mainstream, government-supported Munich Artists’ Association. Munich Secessionists promoted and defended their art in the face of what they considered official paternalism with their traditionalist policies and its opposition to contemporary trends in the art world.

|

| Franz Stuck (1863-1928), Die Sünde (The Sin), 1893 |

The complete financial failure of an exhibition in 1888 added to the separation from the Association and the establishment of the Munich Secession.

The Secessionists declared their intentions to move away from outmoded principles and conception of what art is:

One should see in our exhibitions, every form of art, whether old or new, which will serve the glory of Munich, whose art will be allowed to develop to its full flowering.

These Secessionists transformed what constitutes art and promoted the ideas of artistic freedom to present works directly to the public.

Vienna Secession 1897-1938; 1945-present

|

| Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Friedericke Maria Beer, 1916 |

This movement is closely related to Art Nouveau, formed by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Alphonse Mucha and others. They took their name from the Munich Secession. They disputed artistic nationalism and resigned in protest. They opposed the domination of the official Vienna Academy of the Arts, the Vienna Künstlerhaus, and official art salons, with their time-honoured artistic styles and orientation toward Historicism. The Vienna Secessionists goal states that:

Our art is not a combat of modern artists against those of the past, but the promotion of the arts against the peddlers who pose as artists and who have a commercial interest in not letting art bloom. The choice between commerce and art is the issue at stake in our Secession. It is not a debate over aesthetics, but a confrontation between two different spiritual states.

The movement also established contact, and exchange of ideas with artists outside Austria. They sought to renew the decorative arts, to create a ‘total art’ that unified painting, architecture and the decorative arts.

Their most influential architectural work was the Secession Building, a venue for expositions of the group.

|

| Secession Building, Vienna, (constructed 1897-1898) |

The members split over differing opinions and the movement dissolved as being part of degenerative art by the Nazis in 1938. They re-emerged in 1948 till today.

Berlin Secession 1898-1933

|

| Edvard Munch, The Dance of Life, 1899 |

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Misery, 1897 |

A breakaway group of artists in 1898, led by Max Liebermann (1847-1935), who:

seceded from the city’s arts establishment and founded an independent exhibition society, to champion new forms of modern art – rather than churn out old-fashioned academic art preferred by the Berlin Academy.

|

| Max Liebermann, The Garden of the Orphanage in Amsterdam, 1894 |

|

| Max Pechstein, Under the Trees (Akte im Freien), 1911 |

In 1910, after more radical members emerged and after Liebermann rejected 27 expressionist paintings by artists like Max Pechstein (1881-1955), Secessionist radicals (centred around former members of The Bridge, formed the New Secession, calling themselves ‘Rejected Artists of the Secession Berlin 1910’.

More splinter groups formed in 1913 and 1914, including the ‘Free Secession’.

The official ‘Secession’ had its final exhibition in 1913 but limped on until its dissolution in the 1930s by the Nazis’ degenerate art doctrine.

Die Brücke 1905-1913

|

| Erich Heckel (1883-1970), Weisses Haus in Dangast, 1908 |

The Bridge movement played a

pivotal role in developing German Expressionism, pushing German modern art onto

the international avant-garde scene. The name ‘bridge’ indicated the group’s

desire to bridge the past and present.

It was founded by 4 architectural students in Dresden who had not received any formal education in visual arts. They stressed the value of youth and intuition in escaping the intellectual cul-de-sac of academic thought focused on copying earlier models. These young artists formed an idealistic, communal atmosphere, in which they shared techniques and exhibited together.

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1939), Marzella, 1909-10 |

|

| Albrecht Dürer, Head of an Old Man, 1521 |

|

| Lucas Cranach (the Elder) 1472-1553), An ill-matched pair, c 1530 |

Bridge members developed the modern example of expressive colourists like Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Henri Matisse.

They used violently clashing colours to jolt the viewer into the experience of a particular emotion.

Like the Secessionists, this group sought to create an authentic art that defied the conventions of traditional painting as well as the then dominant schools of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Their painting encompassed all varieties of subject matter—the human figure, landscape, portraiture, still life—executed in a simplified style that stressed bold outlines and strong colour planes.

|

| Otto Mueller, Adam und Eva, 1918 |

|

| Karl Scmidt-Rottluff, Landschaft im Herbst, 1910 |

|

| Fritz Bleyl, poster for the first Brücke show in 1906 |

|

| Otto Mueller (1874–1930), Jahresmappe, 1912, linocut |

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Street (Berlin), 1913 |

The Group held their first exhibition in 1906 in Dresden, by 1911 they shifted to Berlin. However, their volatile relationships increased rifts and they disbanded in 1913.

Today their original prints are highly valued collector’s items.

|

| Emil Nolde (1867-1956), Wildly Dancing Children, 1909 |

Looking at Bridge member Emil Nolde's (1867-1956) painting, I recall seeing pictures by David Boyd, of the renowned Australian artistic Boyd family. Once seen, it is difficult to forget the life-affirming abundance of joy in these paintings.

|

| David Boyd (1924-2011), Dancing Nymphs, 1968 |

|

| King Akhenaton, Queen Nefertiti, 3 of their daughters under the rays of the sun god Aton, altar relief, mid-14th Century BCE |

|

| Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, 1534 |

Portraiture or caricature

|

| Wiliam Dobell, Joshua Smith, 1943 |

Expressionism c 1905–1920

|

Egon Schiele (1890-1918), Portrait of Eduard Kosmack, 1910

The Blue Rider 1911-1914

|

| Wassily Kandinsky, cover of Der Blaue Reiter almanac, c 1912 |

|

| Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, 1906 |

Franz

Marc, Blue Horse I, 1911

|

| August Macke, Lady in a Green Jacket, 1913 |

The outbreak of World War I and the unprecedented devastation that ensued challenged the foundations of many cultures’ belief systems.

This led to a great deal of experimentation and exploration of morality by artists to define what exactly art should be and do for culture. What followed from this was a litany of artistic movements that strove to find their place in an ever-changing world.

Futurism c 1905-1914

|

| Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 |

Perhaps one of the most controversial

movements of the Modernist era was Futurism, which, at a cursory glance,

likened humans to machines and vice versa to embrace change, speed, and

innovation in society while discarding artistic and cultural forms and

traditions of the past. However, at the centre of the Futurist platform was an

endorsement of war and misogyny.

Coined in a 1909 manifesto by Filippo Marinetti, Futurism was not limited to just one art form, but was in fact embraced by sculptors, architects, painters, and writers. Paintings were typically of automobiles, trains, animals, dancers, and large crowds. Painters borrowed the fragmented and intersecting planes from Cubism in combination with the vibrant and expressive colours of Fauvism to glorify the virtues of speed and dynamic movement.

Although originally ardent in their

affirmation of the virtues of war, the Futurists lost steam as the devastation

of WWI became realised.

Cubism c 1907-1914

|

| Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) |

However, the movement did not receive its name until 1908, when, Louis Vauxcelles, who coined Fauvism, depicted some of Georges Braque’s works as being fashioned from cubes.

|

| Georges Braque, Violin and Palette, 1909 |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Girl with a Mandolin, Fanny Tellier, 1910 |

Suprematism c

1913-1923

|

| Kazimir Malevich, Suprematism, 1916-1917 |

Malevich eventually included more colours and shapes, but he epitomised the movement in his ‘White on White’ paintings in which a faintly outlined square is just barely visible.

Suprematism was often imbued with spiritual and mystic undertones that added to its abstraction, and as was the case with Constructivism, the movement essentially came to a complete end as Soviet oppression increased.

Vorticism c 1914-1920

|

| Blast |

|

| Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, 1919 |

However, whereas the Futurists originated in France and Italy and then sprawled out over the continent to Russia, Vorticism remained local in London. Vorticists prided themselves on being independent of similar movements.

When WWI ended and valued Vorticists, namely TE Hulme and Gaudler-Brzeska, died in action, Vorticism shriveled to a small few by the beginning of the 1920s.

Constructivism

c 1915-1920

|

| Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third International model, 1919-1920 |

Dada c 1915-1924

|

| Cover of the first edition of the publication Dada, 1917 |

Dada is based on the recognition and acceptance of the meaninglessness of life, and the last thing Dadaists want to do is to create another illusion to comfort people with a sense of purpose when there is none. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed to be the root cause of the war.

|

| Marcel Duchamps, Fountain, 1917 |

|

| Hannah Höch, The Beautiful Girl, 1919-20 |

|

| John Heartfield, The Meaning of the Hitler Salute: Little Man Asks for Big Gifts, 1932 |

De Stijl c 1917-1931

|

| Piet Mondrian, Composition A, 1920 |

|

| Weissenhofsiedlung, Stuttgart, houses designed by JJP Oud |

Surrealism 1916–1950s

|

| Salvador Dali, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), 1936 |

The term ‘Surrealism’ originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917 and was established in 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by French poet, critic and leader, André Breton (1896-1966), succeeded in claiming the term for his group. The most important centre of the movement was Paris. Politically, Surrealism was Trotskyist, communist and anarchist.

Surrealists

were influenced by Karl Marx and theories developed by Sigmund Freud, who

explored psychoanalysis and the power of imagination.

Its artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and

developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express

itself.

Its aim was, according

to Breton, to:

resolve the

previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute

reality, a super-reality, or surreality.

Influential Surrealist artists like Salvador Dali (1904-1989) tapped into the unconscious mind to

depict revelations found on the street and in everyday life. Dalí’s paintings

in particular pair vivid and bizarre dreams with historical accuracy. Dalí supported capitalism and the fascist

dictatorship of Francisco Franco but

cannot be said to represent a trend in Surrealism in this respect; in fact, he

was considered, by Breton and his associates, to have betrayed and left

Surrealism.

|

| Max Ernst, Ubu Imperator, 1923 |

Many

Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the

philosophical movement first and foremost (eg Breton speaks of the ‘pure

psychic automatism’ in the Manifesto). The works themselves are

secondary, i.e., artifacts of surrealist experimentation. Breton was explicit

in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement.

From the 1920s

onward, the movement spread around the globe, impacting visual arts,

literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as

political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

20th

Century Political Art

|

| Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937 |

While 20th Century Fascism and Nazism followed a destructive artistic agenda, Spanish artist Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) large oil Guernica, one of his best-known works, is regarded by many art critics as the most moving and powerful anti-war painting in history. Picasso painted Guernica at his home in Paris in response to the 26 April 1937 bombing of Guernica, a Basque country town, in northern Spain that was bombed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of the Spanish Nationalists.

Upon completion, Guernica was exhibited at the Spanish display at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, and then at other venues around the world. The touring exhibition was used to raise funds for the Spanish war relief. The painting soon became famous and widely acclaimed, and it helped bring worldwide attention to the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War.

|

| Guernica behind the Prof |

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1950s

|

| Pollock, Jackson, Blue Poles, 1952 |

|

| Mark Rothko, Untitled (Black on Grey), 1970 |

Op Art 1950s-1960s

Heightened by advances in science and technology

as well as an interest in optical effects and illusions, the Op art (short for 'optical' art) movement launched with Le Mouvement, a group exhibition

at Galerie Denise Rene in 1955.

Artists active in this style used shapes,

colours, and patterns to create images that appeared to be moving or blurring,

often produced in black and white for maximum contrast. These abstract patterns

were meant to both confuse and excite the eye.

Coming to the end of this presentation, similar art movements followed and various schools and smaller movements emerged:

Pop Art (1950s–1960s);

Arte Povera (1960s);

Minimalism (1960s–1970s);

Conceptual Art (1960s–1970s) and

Contemporary Art (1970–present).

|

| Gabriele Münter, Landschaft am Meer, 1919 |

List

of Works Consulted

Düchting, Hajo, Der

Blaue Reiter, Taschen, Kőln: 2014

Engels, Sybille,

Trischberger Cornelia, Der Blaue Reiter, Prestel, München, 2014

Grimme, Karin H, Impressionism,

Taschen, Kőln: 2007

Lorenz, Ulrike, Brücke,

Taschen, Kőln: 2008

Moeller, Magdalene M,

The Brücke Museum Berlin, Prestel, Munich, 2014

Néret, Gilles,

Klimt, Taschen, Kőln, 2005

Steiner, Reinhard, Schiele,

Taschen, Kőln, 2004

Ulmer, Renate, Mucha,

Taschen, Kőln, 2007

Wolf, Norbert, Expressionismus,

Taschen, Kőln: 2014

Woolf, Virginia, Mrs Dalloway, Penguin, London: 1992

https://www.ifs.uni-frankfurt.de/english/

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/die-brucke/

https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/political-art

https://www.wikiart.org/en/gabriele-munter

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/dada-and-surrealism/dada2/a/dada-manifesto

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%BCnstlerkolonie_Worpswede

https://en.wikepedia.org/wiki/Die_Brücke

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin_Secession

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich_Secession

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vienna_Secession

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_Academy_of_Arts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salon_(Paris)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Société_des_Artistes_Français

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bridget_Riley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Rothko

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egon_Schiele

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Stuck

https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/the-william-dobell-portrait-that-broke-a-friendship-and-divided-a-nation-20141016-10r84z.html

Images via Wikimedia Commons

Yesterday's revolutionaries are today's classical artists!

Max Liebermann

.jpg)